Down These Mean Streets

By Piri Thomas

Thirty years ago Piri Thomas made literary history with this lacerating, lyrical memoir of his coming of age on the streets of Spanish Harlem. Here was the testament of a born outsider: a Puerto Rican in English-speaking America; a dark-skinned morenito in a family that refused to acknowledge its African blood. Here was an unsparing document of Thomas’s plunge into the deadly consolations of drugs, street fighting, and armed robbery–a descent that ended when the twenty-two-year-old Piri was sent to prison for shooting a cop.

The Woman Warrior

By Maxine Hong Kingston

In her award-winning book The Woman Warrior, Maxine Hong Kingston created an entirely new form—an exhilarating blend of autobiography and mythology, of world and self, of hot rage and cool analysis. First published in 1976, it has become a classic in its innovative portrayal of multiple and intersecting identities—immigrant, female, Chinese, American. A warrior of words, Kingston forges fractured myths and memories into an incandescent whole, achieving a new understanding of her family’s past and her own present.

The House on Mango Street

By Sandra Cisneros

Acclaimed by critics, beloved by readers of all ages, taught everywhere from inner-city grade schools to universities across the country, and translated all over the world, The House on Mango Street is the remarkable story of Esperanza Cordero. Told in a series of vignettes – sometimes heartbreaking, sometimes deeply joyous – it is the story of a young Latina girl growing up in Chicago, inventing for herself who and what she will become. Few other books in our time have touched so many readers.

Create Dangerously

By Edwidge Danticat

In this deeply personal book, the celebrated Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat reflects on art and exile. Inspired by Albert Camus and adapted from her own lectures for Princeton University’s Toni Morrison Lecture Series, here Danticat tells stories of artists who create despite (or because of) the horrors that drove them from their homelands. Combining memoir and essay, these moving and eloquent pieces examine what it means to be an artist from a country in crisis.

-30-

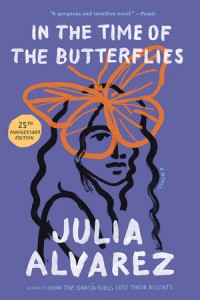

Julia Alvarez believes that stories can change the world.

She ought to know – her deeply empathetic characters and universal stories have resonated the world over, inspiring activists and writers alike to create.

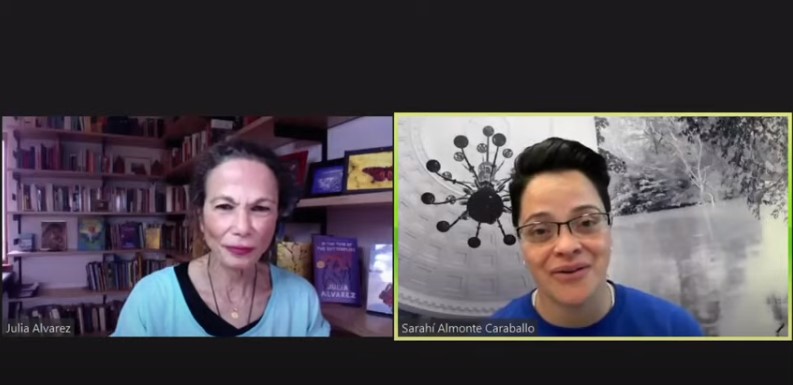

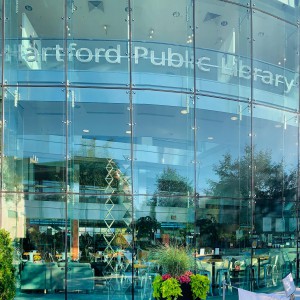

Alvarez spoke to over 300 people from across the world live on Facebook and YouTube on Thursday, March 25 in the conclusion of Hartford Public Library’s month long celebration of her iconic novel “In the Time of the Butterflies.” “It’s a virtual event, but it is as good or better than ever,” said HPL president and CEO Bridget Quinn.

Alvarez and local poet Sarahi Almonte Caraballo had a wide ranging discussion about creativity, the power of stories, and how representation in those stories creates empathy.

First, however, Alvarez gave a brief presentation about her and her inspiration for the novel “In the Time of the Butterflies,” this year’s NEA “Big Read” novel.

Alvarez was born in the United States but her family became homesick and returned to the Dominican Republic when she was young. Her father was the youngest of 25 children, so Alvarez grew up in a happy family bubble, insulated from the realities of life under the dictator Trujillo.

“I had tios and tias and cousins all over the place. It was like a little village … the way I describe my childhood is that I always had a hand to hold,” she said.

While Alvarez grew up in a storytelling culture, one that she believes taught her everything she needed to know, no one read books. An aunt gave Alvarez the single book she had growing up as a child – “One Thousand and One Nights.”

The novel tells the story of Scheherazade, a young woman who staves off the murderous intentions of an evil sultan by telling him a story every night. The resourceful young woman’s stories saved lives because they changed hearts, Alvarez said.

“I wanted to be someone like that. I didn’t know how you did that. It was amazing that stories had that kind of power,” she said.

When Alvarez heard the story of Las Mariposas, the Mirabal sisters who opposed Trujillo and were murdered because of it, she was captivated. “I always thought of them as my sisters who didn’t make it,” she said. “I felt like I owed them something, but I didn’t know what.”

The uprising against Trujillo was an important part of Alvarez’s life story. Her family fled the Dominican Republic to New York because of his involvement in the uprising. She lost family members to the Trujillo regime. It was when Alvarez was introduced to a fourth Mirabal sister – the one her survived – that she realized she needed to tell the story.

“If this isn’t the green light from the powers that be, I don’t know what is,” Alvarez said.

Thanks to Alvarez, the local story of The Butterflies became an international phenomenon. In 1999, the United Nations dedicated November 25 as International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, marking the anniversary of the deaths of the Mirabal sisters.

“I didn’t think the story that I told would help people to find their own Mariposas,” Alvarez said.

Caraballo, a Connecticut resident, poet, nurse and performer, was one of those people. She described Alvarez as a “literary matriarch,” leading the way for Latinx writers to step forward with their own stories and life experiences.

“I’d been trying to find myself in a book for years,” Caraballo said.

Books like Alvarez’s led Caraballo to find her voice as a poet. Caraballo grew up split between English and Spanish, moving between different cultures, different schools. She described herself as a “bridge person,” someone who connected different groups to each other.

“I always say I grew up in transit,” Caraballo said.

There is often an emphasis on books that take us other places. For Caraballo, it was important to find books that took her home. Alvarez’s work, particularly her novel “Something to Declare,” did that for her.

Alvarez said when she was starting out as a writer, there was no such thing as multicultural literature. “It just wasn’t out there. We were trying to find ourselves. The books that we were missing were the ones we set out to write,” Alvarez said.

Alvarez quoted writer Toni Morrison – the function of freedom is to free someone else. Stories are one way to offer freedom and hope.

“I was at home in the world of story. Everyone was welcome. You become the other and the other becomes you,” Alvarez said.

The evening concluded with a tender moment between Caraballo and Alvarez. Julia would turn 71 over the weekend, and Caraballo had written a poem in her honor. It was a piece about a woman finding herself.

“If I didn’t have my makeup, I’d cry,” said Alvarez, visibly moved by Caraballo’s words.

– By Steven Scarpa, manager of communications and public relations

-30-

Spencer G. Shaw knew from his sophomore year at Weaver High School that he wanted to work in a library.

“There was something about it—I just liked it,” Shaw said in an oral history recorded in Hartford Public Library in 2006. A transcript of that recording is available today in the Library’s third floor Hartford History Center.

“I always liked books, as did my sisters and so forth. We liked that, because we had books at home, and we were read to a lot, and so forth. When I used to come out of school, the Northwest Grammar School, on my way home after school I would sometimes dash into the Northwest Library to see what latest sports book was in the collection … if I found a sports book, but I didn’t have my library card, I would run down and hide it behind the history collection! Then go home and get my card, and come back.”

That book-smitten child would go on to become Hartford Public Library’s – and possibly the state of Connecticut’s – first African-American librarian.

In recognition of Shaw’s groundbreaking role, The Black Caucus of the American Library Association – Connecticut Affiliate has announced a scholarship available to an African-American Connecticut resident accepted in an MLS degree program from an ALA accredited Master’s Program in Library and Information Studies.

Interested applicants should visit https://sites.google.com/view/bcala-ct/scholarships/2021-application

Shaw’s work led him well beyond the borders of beloved hometown of Hartford. He received national and international recognition in his field – library service to children – taking him on an exciting professional odyssey: Hartford, Brooklyn, Nassau County, to radio, television and films, to talks and lectures at universities across America and the globe.

“(Shaw is) a leader among librarians and educators, an authentic and forthright spokesperson for children and youth librarians in the State of Washington and the nation, (contributing) enormously in motivating and guiding the nation’s youth,” the American Library Association said about Shaw.

But it all began for Shaw at the Keney Branch Library in 1941. Shaw said it was an exciting time to start a career in librarianship in Hartford. The branch was located at the convergence of Albany Avenue and Main Street in an ethnically diverse neighborhood. It was a working class neighborhood, Shaw recalled, and not immune to racial prejudice. When he was hired, the assistant librarian resigned, something he said she later regretted.

An offhanded remark propelled Shaw into what would become the defining focus of his career – storytelling.

“I shall never forget preparing for that first program. Julia said (Moriarity, Shaw’s assistant), “Spencer, do you want me to do the storytelling, or would you like to do it?” Not thinking very wisely, I said, “Julia, I’ll do it.” So I prepared. And on the day of the first storytelling session, I looked outside the door of the library, which was locked, and saw some children already lining up. This was before television; they had no other place to go!” Shaw said.

He read a version of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarves,” leading him to embrace the universality of fairy tales. Over time, Shaw put together a kind of story hour ritual, with music, candles and beautiful stories from all over the world. He believed that the stories not only gave children a chance to exercise their imaginations, but also as a place to learn empathy.

“From the very beginning, I tried to use the literature, in terms of storytelling, to entertain, yes, but also to lead the listener, or guide the listener, from listening to the book. And also another thing we tried to do through this was to give them the best that there was in literature. And of course, one of my basic uses was to develop a sense of cultural understanding, by stories from different countries,” Shaw said.

It was in Hartford that Shaw began to develop skills he would use the rest of his career. He not only learned the particulars of administrating a library, but he found that he was drawn to working with children. “You learn so much with the children! They can be reached; I don’t care who they are from what background they come,” Shaw said.

Shaw left Hartford Public Library in 1949 and spent the next half-century working throughout the country, honing his storytelling craft. He returned to the greater Hartford area after his retirement, and volunteered as a storyteller at the library well into his late 80s. He died in 2010 at the age of 93.

At the end of his 2006 oral history, Shaw shared a quote he concluded his book talks with. It’s a celebration of what books can give:

“It goes like this, and I’ve always used it … This is by Abbie Farrell Brown. ‘Here’s an adventure. What awaits beyond these closed, mysterious gates? Whom shall I meet? Where shall I go beyond this lovely land I know? Above the sky? Across the sea? What shall I learn, and feel, and be? Open, strange doors, to good or ill! I hold my breath a moment still before the magic of your look. What will you do to me, oh book?’”

by Steven Scarpa, manager of communications and public relations

– 30 -

Hartford Public Library will be reopening its Downtown Library for curated browsing of the collection and socially distanced seating beginning April 19.

The hours of operation will continue to be 9 am to 6 pm Monday-Thursday, 9 am -5 pm Friday and Saturday.

Customers will be allowed to use the library for a two-hour visit period. Self-check machines will be available for customer convenience and safety. Borrowing library materials through HPL’s contact-free service will continue at all library locations. In addition, the Downtown Library will continue to offer dedicated computer use and copying and faxing.

“It’s been a long year, yet we persevered and are emerging on the other side. We were challenged, but persisted and became stronger. And now, we can come back together and continue our path towards a new post-covid reality,” said HPL president and CEO Bridget Quinn.

The Downtown Library will continue to offer appointments for Municipal ID, passport services, and will restore notary services. The American Place and the Hartford History Center will continue to operate by appointment-only for the immediate future.

The third floor children’s room is currently having its flooring replaced and will not be available for public use but materials for children will be available as part of the browsing collection on the first floor. The ground floor will remain available to University of Connecticut students, faculty and staff who have a UConn ID.

There will be a phased reopening of HPL’s neighborhood branches. Beginning in early May the Camp Field Library and Barbour Street Library will open two days per week with other branch locations to follow throughout the upcoming months. Details on the schedule of days and hours will be announced at a later date.

“In our reopening, we will be adhering to measures set by state and local guidelines to safely accommodate you including a mask requirement for staff and the public. We look forward to welcoming our customers back soon,” Quinn said.

- 30 -

Glaisma Perez Silva has muses that inspire her poetry – her identity as a black Puerto Rican woman, her migration from Puerto Rico, the things she sees around her.

When the muses speak, Perez Silva is ready to listen. An idea will arrive and Glaisma will grab whatever she has at hand – even a napkin will work under the right circumstances – to get her thoughts down.

“That’s why sometimes you have to take advantage of the moment or it will disappear and you will say, ‘what was that?’ It is difficult to catch it, or it will come in a different form,” she said. “Once you learn to identify the magic of the moment, the words will flow.”

Perez Silva, a long time Hartford educator, will share her poetry at Hartford Public Library’s Revolutionary Latinas performance, taking place Thursday, March 18 from 7 to 8 pm on HPL’s Facebook and YouTube pages. She will be collaborating with a musician and dancer on a piece about Latina identity, she said.

An educator for the past 40 years, Perez Silva came to Hartford from Puerto Rico in 1988 as part of one of the city’s last bilingual teacher recruitment efforts. “I did not realize I was a poet until I came to Hartford and started feeling the loneliness of being away from my homeland and my family,” she said. “It depends on the circumstances to provoke the muse.”

At first, Perez Silva kept her poetry to herself, ashamed of sharing her words. She branched out slowly, offering her work to a couple of close friends. “When you are sharing your poetry, you are sharing an intimate part of yourself,” Perez-Silva said.

The friends decided to take the leap and present their poetry for a small invited audience. One step at time, the gatherings got bigger, until Perez Silva was part of public performances all around Hartford. “For years I have been evolving in different ways,” she said.

Glaisma writes and performs in Spanish, her native language. It’s important to her to create that way, a small act of cultural rebellion she proudly engages in. She said that when writing in Spanish her voice becomes more concrete and assertive. Her poetry can be demanding and patriotic, and then shift to a tender, mellow, sexy tone.

She is proud of her cultural heritage and deeply respects the way writer Julia Alvarez has represented the uniqueness of the Dominican culture in “In the Time of the Butterflies. “There is a common language, but there are also differences that are unique and make us proud of our homelands,” she said.

By Steven Scarpa, manager of communications and public relations

– 30 –

It started with Patria wanting to be a nun. Mamá was all for having a religion in the family, but Papá did not approve in the least. More than once, he said that Patria as a nun would be a waste of a pretty girl. He only said that once in front of Mamá, but he repeated it often enough to me.

Finally, Papá gave in to Mamá. He said Patria could go away to a convent school if it wasn’t one just for becoming a nun. Mamá agreed.

So, when it came time for Patria to go down to Inmaculada Concepción, I asked Papa if I could go along. That way I could chaperone my older sister, who was already a grown-up señorita. (And she had told me all about how girls become senoritas, too.)

Papa laughed, his eyes flashing proudly at me. The others said I was his favorite. I don’t know why since I was the one always standing up to him. He pulled me to his lap and said, “And who is going to chaperone you?”

“Dedé,” I said, so all three of us could go together. He pulled a long face. “If all my little chickens go, what will become of me?”

I thought he was joking, but his eyes had their serious look. “Papá,” I informed him, “you might as well get used to it. In a few years, we’re all going to marry and leave you.”

For days he quoted me, shaking his head sadly and concluding, “A daughter is a needle in the heart.”

Mama didn’t like him saying so. She thought he was being critical because their only son had died a week after he was born. And just three years ago, Maria Teresa was bom a girl instead of a boy. Anyhow, Mama didn’t think it was a bad idea to send all three of us away. “Enrique, those girls need some learning. Look at us.” Mamá had never admitted it, but I suspected she couldn’t even read.

“What’s wrong with us?” Papá countered, gesturing out the window where wagons waited to be loaded before his warehouses. In the last few years, Papá had made a lot of money from his farm. Now we had class. And, Mama argued, we needed the education to go along with our cash.

Papa caved in again, but said one of us had to stay to help mind the store. He always had to add a little something to whatever Mamá came up with. Mama said he was just putting his mark on everything so no one could say Enrique Mirabal didn’t wear the pants in his family.

I knew what he was up to all right. When Papa asked which one of us would stay as his little helper, he looked directly at me.

I didn’t say a word. I kept studying the floor like maybe my school lessons were chalked on those boards. I didn’t need to worry. Dedé always was the smiling little miss. “I’ll stay and help, Papá.”

Papá looked surprised because really Dedé was a year older than me. She and Patria should have been the two to go away. But then, Papá thought it over and said Dedé could go along, too. So it was settled, all three of us would go to Inmaculada Concepción. Me and Patria would start in the fall, and Dedé would follow in January since Papá wanted the math whiz to help with the books during the busy harvest season.

And that’s how I got free. I don’t mean just going to sleepaway school on a train with a trunkful of new things. I mean in my head after I got to Inmaculada and met Sinita and saw what happened to Lina and realized that I’d just left a small cage to go into a bigger one, the size of our whole country.” (page 11-13)

###

Empezó con Patria que quería ser monja. Mamá estaba entusiasmada con tener una religiosa en la familia, pero papá no aprobaba la idea. Más de una vez dijo que Patria monja sería un desperdicio, pues era muy bonita. Sólo lo dijo una vez delante de mamá, pero a mí me lo repitió muchas veces.

Por fin, papá cedió. Dijo que Patria podía ir a la escuela religiosa si no era sólo un convento. Mamá estuvo de acuerdo.

Así que cuando llegó el momento de que Patria fuera a la Inmaculada Concepción, le pregunté a papá si yo también podía ir. De esa manera podía acompañar y cuidar a mi hermana mayor, que ya era una señorita. (Y me había contado cómo las muchachas se hacen señoritas)

Papá se rió, y se le iluminaron los ojos de orgullo. Las otras decían que yo era su favorita. No sé por qué, pues yo era la única que le hacía frente. Me sentó en su falda

-¿y quién te cuidará a tí?-me preguntó.

-Dedé- dije, para que las tres fuéramos juntas. Él puso la cara larga.

-Si todas mis pollitas se van, ¿qué será de mí?

Pensé que estaba bromeando, pero estaba serio.

-Papá- le informé- es mejor que te acostumbres. En unos cuantos años todas nos casaremos y nos iremos.

Durante días citó mis palabras, meneando la cabeza.

-una hija es una espina en el corazón.

-A mamá no le gustaba que dijera eso. Pensaba que lo decía porque su único hijo había muerto a la semana de nacer. Y hacía sólo tres años había nacido otra niña, María Teresa, y no un varón. De todos modos, mamá no pensaba que era una mala idea enviarnos a las tres a la escuela.

– Enrique, estas niñas necesitan educación. Fíjate en nosotros.-Mamá nunca lo había admitido, pero yo sospechaba que no sabía leer.

-¿qué hay de malo con nosotros?- con un ademán papá señaló la ventana, a través de la cual se veían los carros que esperaban su carga frente a nuestro depósito. En los últimos años, papá había ganado mucho dinero con su granja. Ahora teníamos clase. Y, argumentaba mamá, necesitábamos una buena educación para acompañar nuestra fortuna.

Papá volvió a ceder, pero aclaró que una de nosotras debía quedarse para ayudar con la tienda. Siempre debía agregar algo a lo que decía mamá. Según mamá, lo hacía para que nadie dijera que Enrique Mirabal no era el que llevaba los pantalones en la familia.

Yo me di cuenta muy bien de lo que se proponía. Cuando papá nos preguntó cuál de nosotras se quedaría como su ayudante, me miró directamente a mí.

Yo no dije ni una palabra. Seguí estudiando el piso como si las lecciones de la escuela estuvieran escritas en la madera. No necesitaba preocuparme. Dedé siempre se esforzaba por complacer.

-Yo me quedaré a ayudar, papá

-Papá se mostró sorprendido porque de hecho Dedé era un año mayor que yo. Ella y Patria eran las que debían ir. Pero papá lo pensó mejor y dijo que Dedé también podía ir. Así que quedó arreglado: las tres iríamos a la Inmaculada Concepción. Patria y yo empezaríamos en el otoño, y Dedé se nos reuniría en enero, pues quería que la luz en matemática lo ayudara con los libros durante la atareada estación de la cosecha.

Y así fue como quedé en liberta. No me refiero al hecho de que fui en tren, con un baúl lleno de cosas nuevas, como pupila a una escuela. Quiero decir en mi mente, cuando llegué a la Inmaculada y conocí a Sinita y vi lo que le pasaba a Lina y me di cuenta de que acababa de abandonar una jaula pequeña para entrar en una más grande, del tamaño de nuestro país.» (11-13)

– 30 -

In some ways, becoming a poet was Sarahí Almonte Caraballo’s destiny.

Sarahí is the 33rd of Juana Rivera’s 46 grandchildren. Rivera wrote a little poem on the last page of Caraballo’s baby album.

“I read that poem as a kid and I fell in love with it because, first of all, it’s a poem about you. Right? I remember as a kid knowing that this was something she wrote and I felt special. I loved the way it sounded,” Sarahí said.

At the age of six, her aunt gave her a Hello Kitty journal. Using the letters of Sarahí’s name to start each line, her aunt wrote a poem in the notebook.

With those two anointings, Caraballo’s poetic path was set.

“That’s how I fell in love with poetry,” said Caraballo, who works as a nurse and lives in Wallingford. “I tried to dabble in a little bit of everything but I consider myself primarily a poet and then essayist. Someone said to me a long time ago that I was really good at keeping things short. I like to tell the story and get to the point quicker. I’m not really long-winded so you won’t get a trilogy out of me.”

Sarahí will be interviewing bestselling writer Julia Alvarez on March 25 to conclude the month-long NEA Big Read celebration. “Every Latinx writer knows Julia Alvarez. Julia’s books were the first books that you found that were written by somebody who looked like you, sounded like you, and who had stories that you literally could relate to,” Almonte said.

Caraballo is excited at the prospect of interviewing Alvarez. She’s doing research on Alvarez’s work, looking at previous interviews, and polling her writer friends seeking for questions that will prompt a real conversation.

“I want to ask her everything from, what brought you to writing to what’s the thing that keeps you writing?” she said.

It’s a question that Sarahí herself has a good answer for.

As a teenager, Sarahí started reading poetry. She began writing it shortly thereafter.

Caraballo believes that writing is an act of self-definition. Being published isn’t what’s important. It’s a matter of being willing to pick up a pen every day. “We just need to keep telling our story. If you’re writing in a journal, you’re still writing. If you’re writing on napkins, you’re still writing. Nobody can tell you if you’re a writer but yourself. You don’t need that validation from anyone,” she said.

Writing was Caraballo’s way of learning more about herself.

“I realized that what I thought I was had a name and back in the day you were either gay or lesbian so I picked lesbian,” she said.

Without yet being able to talk about her sexuality, writing became Caraballo’s way to express this important part of herself. “My journal was the place that I turned to write about everything. I knew it was a safe space,” she said.

Caraballo kept writing because she felt that the stories she was reading didn’t reflect her life experience. “Our stories have been either told by others or they’ve been somehow morphed into something that they are not. I realized that our voices need to be heard. We needed more people with our stories on the bookshelves because when we go to library, we like to find things that connect us,” she said.

Caraballo might be looking for advice from Alvarez, but her experience writing heartfelt poetry and essays has given her license to offer wisdom to aspiring writers:

“Just keep writing. Be honest in your writing. You don’t need to make things up. You need to just be honest about your writing and what you’re writing about. It’ll show. There will certainly be a connection,” Caraballo said.

– By Steven Scarpa, manager of communications and media relations

– 30 -

Hartford Public Library announces a new virtual dramatic writing workshop that will give content creators the advice they need to develop their own projects and tell their own stories.

The program, called Talkin’ Drama, will be moderated by Christopher T. Brown, a filmmaker and manager of the Albany Library.

“My passion for storytelling is deeply rooted in my upbringing. Book and films were an important part of my family life. The elders in my family were storytellers who maintained a tradition of oral history to instill morals and values into us as children… All my success as a filmmaker can be traced directly back to my grandmother, her extensive photo albums, and the stories I heard as a child surrounding those pictures,” Brown said.

The program will take place on the last Thursday of every month. Each workshop will feature a guest speaker or panel made up of industry professionals. After the presentation, there will be an opportunity for viewers to ask questions of the panelists.

The first workshop, featuring cinematographer Jeremy Royce, is scheduled for Thursday, March 25, 2021 from Noon – 1 pm on Zoom.

“My plan is to approach everyone that I know in Hollywood who I think could make on impact on the Hartford community to be a guest on Talkin’ Drama. The more I can act as a bridge between Hartford and Hollywood, the better,” Brown said. “The goal is to encourage people to read, and use the library.”

Royce graduated from USC’s school of cinematic arts in 2013. His work has been short-listed for a student Academy Award and nominated for a student Emmy and has earned him multiple awards for directing and cinematography. Jeremy’s debut feature film ‘20 Years of Madness’ premiered at the 2015 Slamdance Film Festival in Park City where it won the Jury Honorable Mention. Jeremy currently works as an LA based freelance cinematographer and teaches part time at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts.

Artists and creators will discuss the mechanics of dramatic writing as it functions in their career, and discuss benefits and pitfalls of developing content. It will dive into the practical and real issues facing someone as they develop their artistic craft. They will highlight ways teamwork functions in the process of storytelling. In addition, the Talkin’ Drama series will cover the practical aspects of why it is essential to be entrepreneurial within the ever-changing landscape of the entertainment industry.

Whether you strive to be a content creator, producer, writer, director, playwright, attorney, or entrepreneur, this workshop will help you identify the path towards creating meaningful stories.

Brown, a Hartford native and Trinity College and NYU Tisch School of the Arts graduate, was recruited to HPL as a branch manager of Albany in 2020, from Los Angeles. He has also made short films set in Hartford.

“I ran a Talkin’ Drama workshop at Milner Vine Street school in 2019. The program was a huge success, so I thought it was only right I introduce it to HPL adult virtual programming. It could fit within the scope of our virtual limitations. And it gives Hartford natives access to professionals actively working in Hollywood,” Brown said.

In addition to his own films, Brown’s work in the industry spans back to 2006, starting as a script reader for Samuel Goldwyn Films. He was later honored in 2011, with a nomination for a Kennedy Award for a play he’d written entitled, Tough Love. While at New York University, he began working with Spike Lee, working on several projects with him including Michael Jackson Bad25 and Da Sweet Blood of Jesus. Brown was a production assistant on The Birth of a Nation (2016), a producer on the television pilot “Baselines” (2018). And the second unit director on Final Frequency (2019).

-30-

Managing extensive collections of print and non-print materials is something that goes on every day at libraries around the world. At the Hartford Public Library, trained library employees are continuously assessing and reviewing new and old materials to keep the collections current, make room for new materials, and make sure our valuable shelf space is being used to its best advantage to provide the information our users want and need.

Deaccessioned books are either sold to raise funds for the library, or distributed throughout the community from the Library on Wheels, Community Collections or Little Free Libraries.

Carol Pugh, a library assistant, has found yet another way for those discarded books to find a good home.

Pugh, a HPL staff member since 2019, has been taking deaccessioned books from the collections and sending them through the Connecticut Prison Book Connection, to people who are incarcerated. Each month Pugh receives about 20 to 25 requests from prisoners, most coming from her home state of Texas, and Florida. There are occasional requests from Connecticut based inmates, she said.

“It’s a great feeling. I absolutely love doing it,” Pugh said.

“Knowing how difficult it can be for prisoners to get their hands on books, let alone books they are interested in, makes what Carol is doing even more meaningful,” said Marie Jarry, HPL’s director of public services.

Depending on what the request is, Pugh is able to send two or three books to each person. She does face some restrictions on what she can share. Hardcover books, for instance, can be banned. Prisons will also limit certain kinds of content.

Despite the roadblocks, there is a desire for books that Pugh can help fulfill.

“A lot of these guys and women don’t read unless they’re locked up,” Pugh said. “With COVID putting most facilities in 24/7 lockdown, this is a way for them to get their mind off of being enclosed in a small cell. They can use their imagination and escape through these books.”

Pugh gets requests for a little bit of everything, but true crime, romance, and self-help books are the most desirable. Some inmates will request thesauruses and rhyming dictionaries to help with their poetry or rap lyrics.

She makes an effort to make sure every request gets fulfilled. For example, the works of author James Patterson are popular, but Pugh might not have access to his titles that particular week. So, she’ll substitute, replacing Patterson with an author likeDavid Baldacci– a read-alike, as she described it. If an inmate’s letter is filled with spelling mistakes or grammar errors, she’ll send along a dictionary too.

Her interest in working with the incarcerated goes back to her days in Texas volunteering at the Travis County Correctional Complex’s library. She saw how the prisoners craved the written word and treated the materials and the library staff members with respect. Pugh also noticed that the library often didn’t have the books the incarcerated people really wanted.

“These people are usually forgotten about. Sending books to them is a is a way for them to know that people really do care. Not just their physical being, but their minds,” Pugh said. “It’s important to me to help them learn and grow and use the time behind bars so they don’t make the same mistakes that got them in there.”

Pugh’s long term aspiration is to work in a prison library. “I’ve always loved libraries. I find them peaceful and you can learn so many different things. You can escape from reality in a good book,” Pugh said.

– By Steven Scarpa, manager of communications and public relations

– 30 -

Poet Diana Aldrete thinks of her poetry as being like a Polaroid – a moment in time.

She then takes that moment and explores the imagery inside of it, teasing out the feelings. She puts pen to paper, and then tests her words out loud.

If she’s done her job well, she draws the reader and the listener into her world.

Aldrete, a Hartford resident, will be performing an original work in Spanish and English at the opening event of the NEA Big Read on Sunday, February 28 at 3 pm. “Typically when I am writing a poem it only comes out in one language. This one is going to be very interesting,” she said.

Aldrete, a visiting lecturer of language and culture studies at Trinity College, began writing poetry in high school. As first generation American whose parents were born in Mexico and El Salvador, language was a central part of Aldrete’s formative experiences.

“Language is big. It’s huge. And I think that’s what connects my entire work, my entire identity. Spanish language is my first language. My parents spoke to us in Spanish,” Aldrete said.

She was born in the United States, but moved back to Mexico for a time, where she and her family spoke only Spanish. Aldrete returned to the United States, returning to English as her primary language.

“When I took my first Latin American literature class I felt like I returned home. I was reading my language in these beautiful art forms – novels, poetry, and essays – I fell in love with it. It has informed the way I think and the way I write. Using Spanish in my art is an homage to that experience,” she said.

Aldrete has always been a creative person, but it wasn’t until she began teaching literature that she re-engaged with poetry and began thinking of herself as a performer. “I started to get inspired by the poets that I was teaching. Then I would start writing my own poetry and developing my own style,” she said.

“I am a fan of hers. I have taught her for novel in my classes … not only am I a fan of the book, but also what it stands for as far as championing and advocating for women’s rights, especially in times of oppression,” Aldrete said.

The novel tells the story of three sisters, known at The Butterflies, who opposed the dictator Trujillo and paid with their lives. Aldrete believes that the novel has contemporary resonance. “We see this in terms of women’s issues. We saw the Women’s March, women joining together in solidarity to speak out against sexism and oppression in many forms. I think (the novel) really speak to where we are,” she said.

It’s about more than just the story for Aldrete. The way that Alvarez plays with language to evoke the beauty of the Dominican Republic is an inspiration. “It felt familiar to me. Some of the things I remember from living in Mexico. I felt connected to that because of her use of the language. I feel the sensory images. I am really connected to her work because of that,” Aldrete said.

To learn more about Aldrete’s work, visit her here: https://linktr.ee/aldreted

– by Steven Scarpa, manager of communications and public relations

-30-